This is amazing. We don't have any way to know it, short of multiple DNA and/or blood tests, but many of us might actually be fused twins!

DNA Double Take

Noah Berger

New York Times

September 16, 2013

From biology class to “C.S.I.,” we are told again and again that our genome is at the heart of our identity. Read the sequences in the chromosomes of a single cell, and learn everything about a person’s genetic information — or, as 23andme, a prominent genetic testing company, says on its Web site, “The more you know about your DNA, the more you know about yourself.”

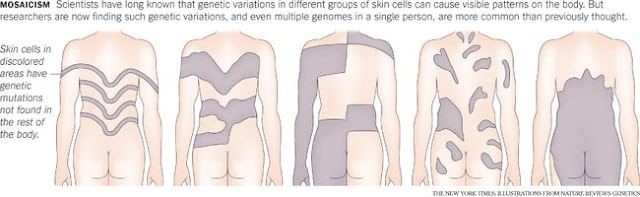

But scientists are discovering that — to a surprising degree — we contain genetic multitudes. Not long ago, researchers had thought it was rare for the cells in a single healthy person to differ genetically in a significant way. But scientists are finding that it’s quite common for an individual to have multiple genomes. Some people, for example, have groups of cells with mutations that are not found in the rest of the body. Some have genomes that came from other people.

“There have been whispers in the matrix about this for years, even decades, but only in a very hypothetical sense,” said Alexander Urban, a geneticist at Stanford University. Even three years ago, suggesting that there was widespread genetic variation in a single body would have been met with skepticism, he said. “You would have just run against the wall.” ...

In 1953... a British woman donated a pint of blood. It turned out that some of her blood was Type O and some was Type A. The scientists who studied her concluded that she had acquired some of her blood from her twin brother in the womb, including his genomes in his blood cells.

Chimerism, as such conditions came to be known, seemed for many years to be a rarity. But “it can be commoner than we realized,” said Dr. Linda Randolph, a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles who is an author of a review of chimerism published in The American Journal of Medical Genetics in July.

Twins can end up with a mixed supply of blood when they get nutrients in the womb through the same set of blood vessels. In other cases, two fertilized eggs may fuse together. These so-called embryonic chimeras may go through life blissfully unaware of their origins.

One woman discovered she was a chimera as late as age 52. In need of a kidney transplant, she was tested so that she might find a match. The results indicated that she was not the mother of two of her three biological children. It turned out that she had originated from two genomes. One genome gave rise to her blood and some of her eggs; other eggs carried a separate genome.

Women can also gain genomes from their children. After a baby is born, it may leave some fetal cells behind in its mother’s body, where they can travel to different organs and be absorbed into those tissues. “It’s pretty likely that any woman who has been pregnant is a chimera,” Dr. Randolph said.

Everywhere You Look

As scientists begin to search for chimeras systematically — rather than waiting for them to turn up in puzzling medical tests — they’re finding them in a remarkably high fraction of people. In 2012, Canadian scientists performed autopsies on the brains of 59 women. They found neurons with Y chromosomes in 63 percent of them. The neurons likely developed from cells originating in their sons.

In The International Journal of Cancer in August, Eugen Dhimolea of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and colleagues reported that male cells can also infiltrate breast tissue. When they looked for Y chromosomes in samples of breast tissue, they found it in 56 percent of the women they investigated.

No comments:

Post a Comment